On the Unbalanced Coverage of the XueBing Case

This article was republished from:https://madeinchinajournal.com/2024/07/23/on-the-unbalanced-coverage-of-the-xuebing-case/

On 14 June 2024, the verdict in the case of Chinese feminist activist and independent journalist Huang Xueqin and labour activist Wang Jianbing (hereinafter referred to as the ‘XueBing case’) was finally announced. Both had been accused of ‘inciting subversion of state power’. After nearly 1,000 days of arbitrary detention, Huang was sentenced to five years in prison and Wang to three years and six months. Before being detained, Huang and Wang had organised regular gatherings and engaged deeply with activist communities in Guangzhou to rebuild civil society networks that had been suppressed for years. The authorities saw these efforts as a potential threat. The sudden arrest of the pair represented another major political crackdown by the Chinese Government on Guangzhou’s once vibrant civil society and highlights a shift in the focus of repression towards underground civil society networks.

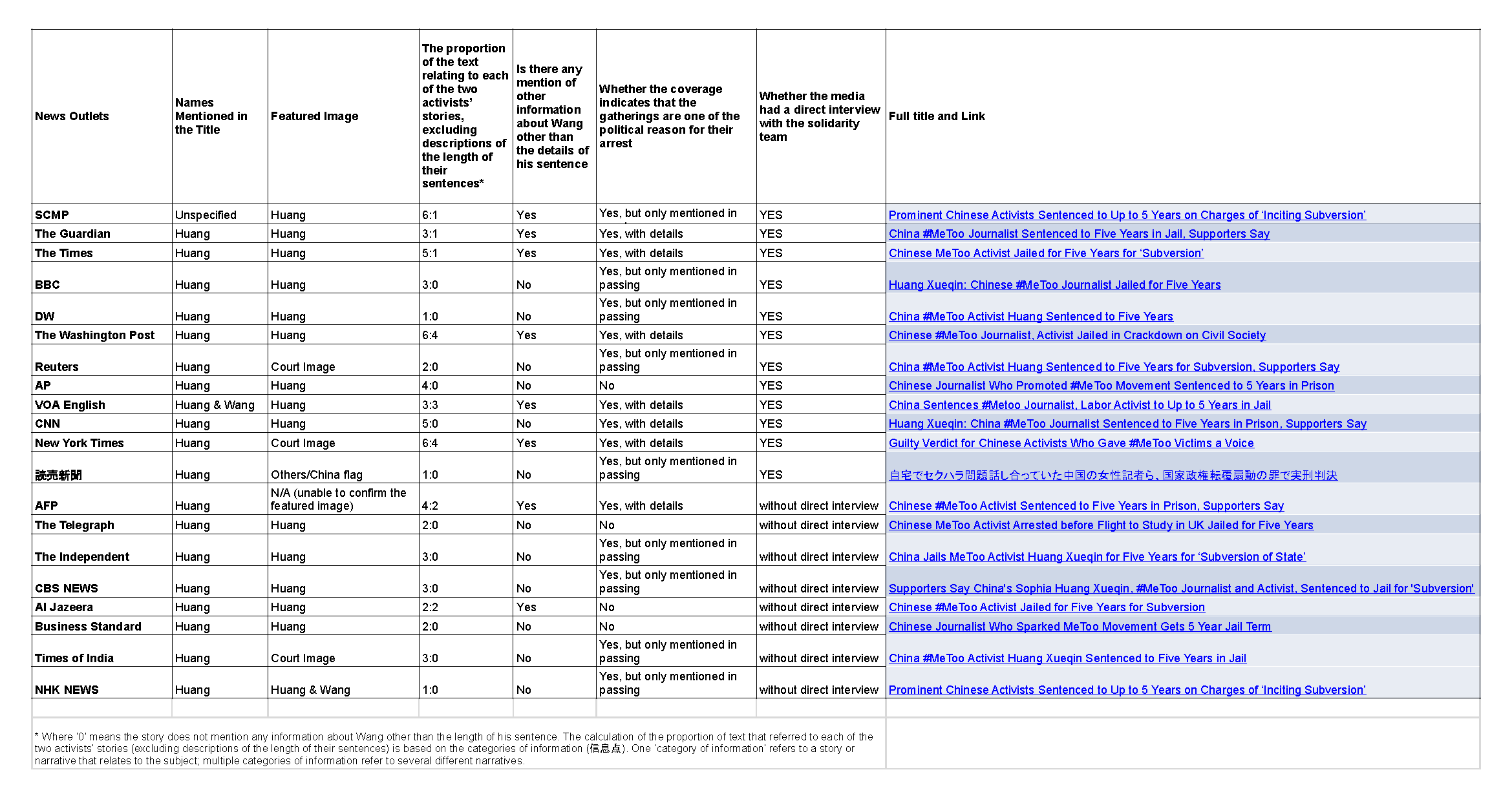

Unfortunately, we have observed that there are significant imbalances and biases in media coverage of and solidarity campaigns surrounding the XueBing case that fail to accurately reflect the political significance of the case and the contributions of both individuals to social movements in China. After the verdict, several major international news outlets published stories about the case. For this op-ed, we conducted a systematic analysis of 20 original media reports in English and Japanese. Twelve of the selected reports feature direct interviews with the Free XueBing group, while the other eight are reports that rely on syndicated material and statements from the group or human rights organisations. To avoid redundancy, we did not consider other articles that do not include original reporting. Given that reports in Chinese-language media (mostly from Hong Kong and Taiwan for political reasons) often rely on syndicated material from other sources, it is reasonable to expect that coverage of the XueBing case in the Chinese-language press was significantly influenced by the reports from the major media outlets they reference, including the ones in our sample, but this is outside the scope of our analysis.

Our analysis reveals that none of the media reports in our sample mentioned both Huang Xueqin and Wang Jianbing in their headlines or in their featured images, even though both were co-defendants in the case. Overall, the media coverage was heavily skewed towards coverage of feminist activist Huang, with 12 reports making no mention of Wang other than his prison sentence; his name was mentioned only in passing. In the reports that covered both, the content on Huang took up far more space than that on Wang (more than three times as much on average). Even in the stories about Huang, the focus was exclusively on her role in advancing the #MeToo movement in China, while the important factors related to the charges against both individuals—such as their fight for freedom of speech and the right to organise community gatherings—were not mentioned at all by four foreign-language media outlets and glossed over by most of the others. Similar issues are also present in some of the solidarity campaigns.

This imbalance and skewed focus are both disheartening and deeply troubling, as they not only oversimplify or disregard the contributions of Chinese activists, but also highlight a lack of reflection in current discourse on the hierarchies embedded within social resistance. A similar situation can be observed in Hong Kong’s ‘47-person case’, in which the public discussions focused mainly on a few well-known activists involved in overtly political issues and neglected the others. This opinion piece takes the unbalanced coverage of the ‘XueBing case’ as a starting point to reflect on the problems that exist in the mainstream media’s coverage of social resistance today.

Who Are XueBing and What Led to Their Arrest?

On 19 September 2021, Huang Xueqin and Wang Jianbing were taken from the latter’s apartment by Guangzhou police and placed in solitary confinement. It was later reported that they were detained on suspicion of ‘inciting subversion of state power’. Huang is known for her role in sparking the #MeToo movement in China by exposing a sexual harassment case involving a professor at Beihang University (Lin and Mai 2024). In 2019, she was placed under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL)—a coercive measure often used by the Chinese authorities to suppress human rights defenders, who are held in secret solitary confinement and interrogated under torture, without access to lawyers or family members—for three months for her reporting on Hong Kong’s ‘Anti–Extradition Law Amendment’ movement. Wang is a low-profile, veteran non-profit worker and dedicated labour activist largely unknown to the public (Lin 2024). After graduating from university, he became involved in non-profit work, initially focusing on rural development and education for left-behind children in rural areas of northwest China. Later, he moved to Guangzhou to work on the development of civil society organisations and the empowerment of people with disabilities. Since 2018, he had been working on rights advocacy and community organising among migrant workers with occupational diseases—a politically sensitive issue in China even though it does not attract much public attention.

Before their arrests, Huang and Wang organised regular gatherings in Guangzhou to try to rebuild the civil society networks that had been suppressed for years. After several political crackdowns, Guangzhou’s once vibrant civil society community had become dormant and activists felt isolated and atomised. The gatherings the pair organised were meant to break this deadlock by providing a safe space for young activists and regrouping like-minded activists. However, the renewed vitality and activism of their efforts apparently caught the attention of the authorities. The indictment and verdict clearly show that the government framed the gatherings organised by Huang and Wang as attempts at creating a ‘non-violent movement’—a term that has long been vilified in the official discourse of the Chinese authorities because they see it as closely associated with colour revolutions—and their expressions on social media and at gatherings were classified as having ‘seditious’ intentions (for the indictment, see Guangzhou Procuratorate 2022; for the verdict, see Guangzhou Intermediate Court 2024). Although the gatherings did not involve explicit political antagonists, the community network they fostered and the social criticism they spawned were seen by the authorities as destabilising factors that threatened national security.

Overlooked Contributions to Social Movements

As mentioned above, the weekly gatherings organised in Guangzhou were a significant political factor in the harsh sentencing of XueBing. These longstanding gatherings served as both an indirect response to the oppressive political environment and a new form of social resistance strategy. However, many reports have overlooked this crucial detail, disregarding the efforts of XueBing in rebuilding activist communities in China and omitting a very significant detail from the documentation of Chinese social resistance.

The criminalised weekly gatherings were initiated by Wang and later co-organised with Huang and another co-defendant surnamed Chen whose case is being handled separately. Wang recognised the necessity of creating a space where young people could support each other through challenging times and explore new forms of connection and activism. Therefore, he started the weekly gatherings in his living room, calling them ‘Night-Sailing Boat’ (夜航船) to symbolise how activists navigating through dark times could find direction and strength through mutual support—an ideal he shared with Huang. Wang had also tried to use this approach to organise a community for the support and empowerment of migrant workers suffering from pneumoconiosis.

Before the gatherings, Wang would be busy preparing fruit, snacks, and tea for the participants and he would clean up afterward. During the gatherings, Wang served as a facilitator, ensuring that each participant had the opportunity to express and discuss their concerns or ideas. Huang, meanwhile, focused more on theme planning and discussions. This strategy of empowerment, which focuses on underground, close-knit communities, can help reconnect China’s fragmented civil society. In fact, we saw the same organising strategy in the White Paper protests in late 2022, where the protesters who were later targeted by the government had rich underground support networks. Unfortunately, these community organising efforts received no media attention.

Aside from the dearth of coverage of Wang’s labour activism, most reports on Huang focused solely on her involvement in the #MeToo movement in China, thereby overlooking her personal efforts in advancing civil society networks, such as her pivotal role in the ‘Night- Sailing Boat’ gatherings and efforts to build activists’ capacity through initiatives such as the ‘Ten Lessons’ (十堂课) workshops, which were a series of online gatherings she started a year before her arrest to which she invited scholars and activists to discuss the hot topics of the day. The media’s coverage of Huang’s involvement in the #MeToo movement as the primary reason for government prosecution not only leads to a significant public misunderstanding of the case but also disregards her broader contributions to nurturing activist communities.

Devaluing Low-Profile and Behind-the-Scenes Contributions

The implication of this oversimplified coverage of social resistance is that low-profile grassroots efforts are merely supplements to or less important than high-profile activism—a narrative that devalues fundamental behind-the-scenes work.

Despite his low profile, Wang’s significance in community organising in this case should not be overlooked. His efforts to organise the weekly gatherings exemplify the often-unseen labour and care work that is essential for the sustenance of social movements and paves the way for broader, more visible actions. To ignore Wang’s pivotal role not only disregards the foundational efforts of less-visible activists, but also exposes a bias rooted in misogynistic and patriarchal norms; care work in activism is often socially gendered and undervalued. It is important to clarify that this does not mean that care work in activism is done only by women. Rather, it reveals the irony of coverage that highlights movements like #MeToo, while inadvertently replicating the very norms they seek to challenge.

A low profile should not be an excuse to deny activists social recognition and respect. However, the lack of balanced reporting perpetuates the mainstream narrative that only high-profile or well-known activists deserve acknowledgement. This phenomenon contradicts the media’s goal of promoting social justice, which includes challenging the criminalisation and devaluation of social resistance by authoritarian governments and highlighting the value and contributions of activists facing unjust trials. This problem extends well beyond XueBing’s case. Many forms of social resistance remain unseen, particularly those involving female activists or focusing on marginalised issues such as labour rights or disability. Additionally, the behind-the-scenes, grassroots work done by less-visible activists—the backbone of social movements—is often overshadowed by high-profile actions.

Identity Politics in Solidarity Campaigns

Furthermore, we notice an imbalance in the solidarity campaigns around the XueBing case. Some focus exclusively on Huang’s involvement in the #MeToo movement, neglecting to acknowledge Wang as a co-defendant. While it is understandable that these campaigns are being conducted under the banner of feminist advocacy and that identity politics is an important tool for social mobilisation, Wang’s history of supporting survivors of sexual harassment—despite being extremely low profile—has been overlooked in these efforts.

As advocates and activists, it is important to recognise that an attack on one is an attack on all, especially amid ongoing repression of human rights defenders, whether feminists or labour activists. When, as is often the case, issues involve clear diversity and intersectionality, prioritising certain identities over others in advocacy can inadvertently create divisions within the activist community and undermine the solidarity and collective power needed to challenge oppressive systems. Solidarity means respecting one another’s dignity and integrity while addressing shared structural oppressions together, rather than competing for recognition or validating individual agendas. While leveraging campaigns to advance one’s own agenda is a common strategy, it is crucial to avoid diminishing or neglecting other groups or behind-the-scenes work. Such oversights undermine the very solidarity that social movements seek to build and should be avoided in solidarity campaigns.

Reflecting on the Roles of the Media and Social Advocacy

Some may attribute the lack of media coverage about Wang and the criminalised gatherings to the low-profile nature of his activism and the limited information that is publicly available. However, both the media and campaigners have a responsibility to understand and communicate the complexity of resistance movements and to challenge oversimplified or distorted narratives of social resistance by those in power. It is certainly comprehensible why the media focuses on Huang given that she gained her prominence through her involvement in the #MeToo movement; it makes it easier to convey to readers the extent of the Chinese State’s persecution of human rights defenders and requires less editorial work than uncovering Wang’s story and building a narrative around the gatherings they organised. This approach, however, at least from an activist’s perspective, is not conducive to presenting a complete narrative of resistance.

On the one hand, such reporting tends to oversimplify specific forms of social resistance in China, reducing them to mere instruments and reinforcing some readers’ one-dimensional perceptions of Chinese politics. This oversimplification not only misrepresents social resistance but also undermines the agency of the subjects of this coverage. On the other hand, the media’s market-oriented model and lack of comprehensive coverage of complex social resistance raise concerns about its effectiveness in educating the public. XueBing’s case highlights this issue, as its significance extends beyond the realms of feminism and labour rights to include new organising strategies, such as the formation of underground networks and the practice of community empowerment. The media’s failure to document this represents a significant flattening of social resistance in China today.

In addressing the imbalance and skewed focus of the media coverage of the XueBing case, it is important to clarify that we do not intend to undermine the support and impact of the media and solidarity campaigns for these individuals and broader Chinese human rights struggles. Rather, our aim is to highlight how the lack of discussion of the politics behind their arrest and sentencing, the devaluation of low-profile activism, and the disproportionate attention on identity-politics–driven mobilisations do not do justice to the current landscape of social resistance in China. This imbalance also reflects a microcosm of embedded hierarchies that characterise social struggles in society. We call on the media to reflect on its educational role and adopt a more balanced and nuanced approach to documenting such cases, as these reports can serve as an important reference for future social resistance. Providing balanced and nuanced attention to activists and social struggles, regardless of their visibility or profile, is the first step towards building a more inclusive and progressive social movement for change in China.

Appendix: Statistical Analysis of Media Reports (PDF Version)

References

- Guangzhou Intermediate Court. 2024. ‘广东省广州市中级人民法院刑事判决书 [2022] 粤01刑初298号 [Criminal Sentence No. 1/298, by the Guangzhou People’s Intermediate Court, Guangdong Province].’ Available online at cryptpad.fr/file/ – /2/file/DvaYZGmu69bttv1ZOsWuj5Ud.

- Guangzhou Procuratorate. 2022. ‘广东省广州市人民检察院起诉书 穗检刑诉 [2002] Z11号 [Indictment No. Z11/2022, by the People’s Procuratorate of Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province].’ Available on the Free Huang XueQin & Wang JianBing campaign website. free-xueq-jianb.github.io/2023/09/23/qisushu.

- Lin, Yaming. 2024. ‘Subverting the Status Quo.’ Asian Labour Review, 7 July. labourreview.org/subverting-the-status-quo.

- Lin, Yaming, and Diuti Mai. 2024. ‘Who Is Huang Xueqin?’ WOMEN我们, 25 January. women4china.substack.com/p/who-is-huang-xueqin.